In the world of screenwriting, your logline is a handful of words that stand between you –the writer– and your script’s potential success.

This is a long article about loglines; mainly explaining why you need them and how they must be perfect.

If you want more concrete info on “how to write a logline,” skip to the bottom and follow the links. Stick around for a read if you want to understand the whys and wherefores as well as a little history and context.

English is tricky. And English jargon even more so.

Like every specialized activity or job, the world of screenwriting –amateur or otherwise– enjoys its own insider lingo. And it’s one we all need to strive to speak and understand.

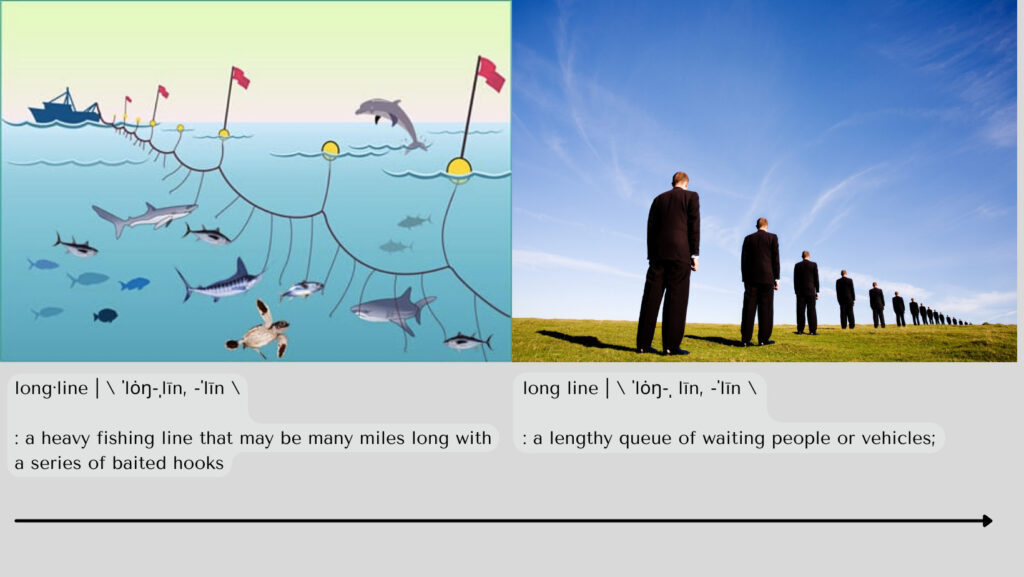

One of the first new words you’ll learn is “logline.” Not longline, in spite of the default autocorrect. It’s a logline. You’ll want to train your devices to recognize the word.

A longline is a type of deep-sea commercial fishing technique that drags on the bottom of the ocean. Whereas a long line is a lengthy queue of people or cars.

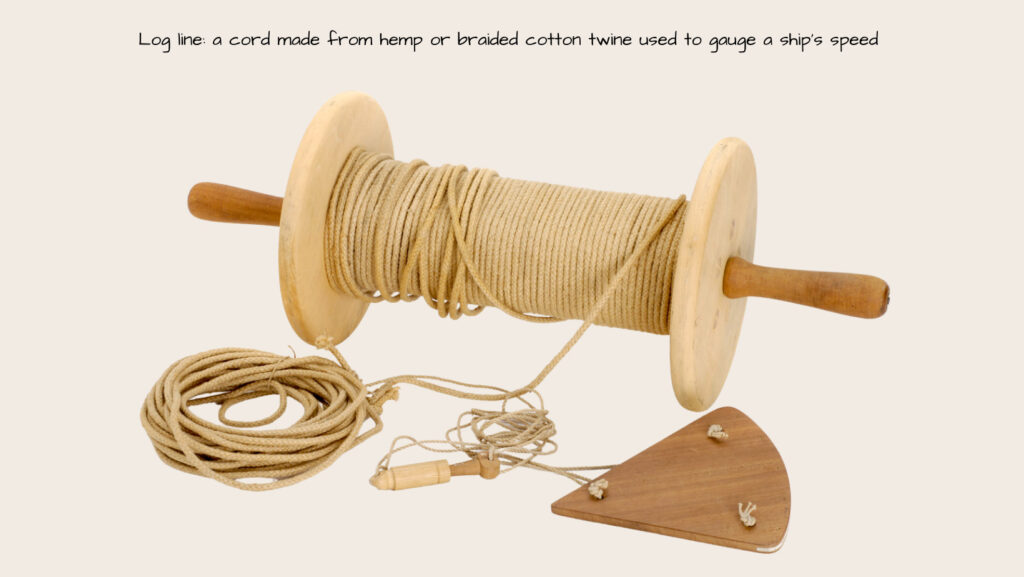

Also from the oceanic world, the term log line describes an analog nautical device used to measure the speed of a sailing vessel.

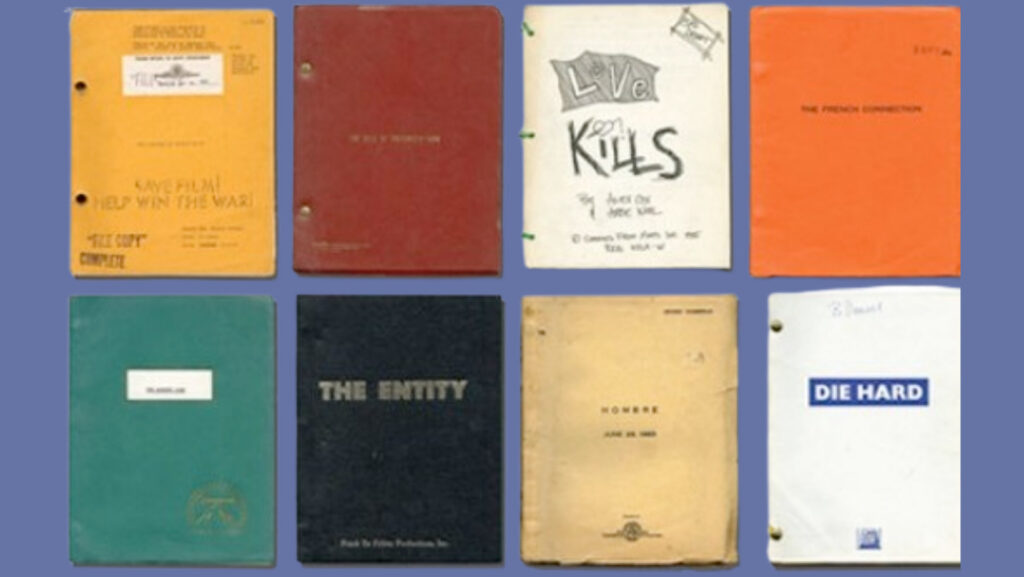

But, according to Hollywood lore, the word logline in that world hails back to the early days of film when the big studios all used logbooks to track the scripts they owned. When a studio purchased a new script, someone was in charge of logging it into the book by hand, noting the title, writer, date, and a short description: i.e. the “log” line.

The actual physical scripts were kept elsewhere in libraries. I sometimes imagine those early script vaults like police evidence rooms. At least in the sense that there was a written record of everything filed there, but no one really knew where exactly to find them.

The only way to find them was to refer back to the original logbook. The words listed there, in ink, would be the script’s permanent description. I’m quite certain that back then there was an underground group that worked with the secretaries of the day to get the ‘right’ logline recorded in the book.

I repeat: the words in your logline are likely the key to your script’s ultimate success.

Your logline is a weighty piece of craft

It’s that important. And too often misunderstood. And unappreciated. In fact, the logline, I’m learning more and more, is a weighty piece of craft indeed.

Many new and intermediate writers discount the value of these few words, to their own peril. They think, as I once did too, that it matters so little they can hastily cobble together a few words on the fly, just as they’re submitting to AFF at the 11th hour or when they respond to a specific call.

Think about it. You need a logline for everything. A contest entry, script hosting sites, your elevator pitch, and even when you’re posting in a screenwriting forum looking for a script swap. Your logline is the single most important sales tool for your story.

If your logline is posted on InkTip or Blcklist or Script Revolution or Zoetrope, you want it to stimulate the reader to at least take the next step: to read the synopsis.

If you don’t get synopsis reads, there’s something wrong with your logline. It’s that simple.

Harder to write than you might think

I’ve written quite a bit about loglines, especially in the past couple of years. I used to think they came more easily to me than others because of my early career as a print journalist. Loglines were nothing more than longish versions of headlines, I surmised. Or like an overly detailed lead. So I thought.

But I came to understand that’s only true to a certain extent. Look at this headline: Five commuters killed in train wreck. That’s an event. It’s not a story. Headlines focus on who and what happened.

In fact, the train wreck in a logline would reveal only the inciting incident and need more than five times as many words to make a logline. Like this: When a train wreck kills both her parents and jolts her system, a teenage mutant must hide her now awakened powers from the organization that seeks to hunt her down and kill her.

A headline is five to 10 words. A logline is around 25-50 words, depending on who you ask. (Even 60 words, but aim for 35.) So, a logline comprises many more words than a headline.

Then there’s the tagline; which is another animal entirely.

A headline objectively tells what happened. Whereas a logline needs to say what will happen (stakes) unless a specific hero overcomes certain obstacles/antagonists. Ticking clocks exist in both. The tagline, on the other hand, plays a teasing, not informative role.

Make a pro script reader’s day

Take a look at these examples for the same (fictional) story:

- Headline: Congress has until Friday to pass controversial Space Force budget (10 words)

- Logline: When a disbelieving Congress ignores an extinction-level earthbound meteor, a frantic astronomer struggles to avoid detection in a race against time to plant an illegal device that will save the planet. (31 words)

- Tagline: Sometimes the only solution is to break the law. (9 words)

None are easy to get right. Especially the logline. And –once again, sorry for the multiple rinse-and-repeat instructions– they are absolutely critical to your success as a screenwriter. Anyone who tells you otherwise must have had an outlier experience.

Without an excellent logline that makes the reader sit up and pay attention, you will not get a read-request. So, again, unless you’re really writing screenplays “just for fun” and you never intend to even enter a contest, you need to pay attention to the loglines you write.

Why not give it your best possible effort to write a fantastic logline that makes a hungry reader salivate? Remember this: Readers love the very idea of finding a diamond in the rough. Make their day.

The myth that loglines don’t matter

I cannot stress this enough. It truly would behoove you to learn the craft and learn it well. In fact, I highly recommend you budget some focused learning time every week on nothing but loglines.

Here are a few vetted resources to get you started. Even if you read only one of those articles and watch one video a day for the next few days, you will be better prepared. And you will understand why these few words are so important to your entry.

Still unconvinced? Your logline for your IP is the calling card for your screenplay. It’s that simple. It’s your brand.

Imagine an independent production company is looking for a particular kind of script, say an imaginative holiday romcom, like “The Holiday meets Love, Actually.” They send their underlings to Coverfly, Blacklist, and Inktip to scour. They’re happy to entertain the idea of unknown writers.

The staff person plugs in the genre and any other details they can into the database to narrow it down, depending on the platform. (e.g. some can drill down to things like “strong female lead” or the number of locations.)

Your script title pops up on a long list. That low-level script reader’s task is to peruse dozens, or scores, of loglines and identify potential stories for their company’s possible interest.

If yours stands out they’ll add it to their list and read your synopsis. Then, provided it matches the logline and fits what they’re looking for, they’ll download your script.

If your logline stands out…

Are you grasping the absolutely critical nature of nailing each one of those words?

Christopher Lockhart, someone you may want to get to know, runs perhaps the most encouraging and civil Facebook group to support creatives (The Inside Pitch). He confesses that he doesn’t even read a script’s title before deciding whether to delete the email.

He just reads the logline.

If the logline intrigues him, he’ll read the email. And at the end of the day, he just might ask to look at the script.

Chris looks for three things in a logline.

- CONCEPT: (A tidal wave capsizes a ship, turning it over)

- CHARACTER: (A rebellious preacher)

- CONFLICT: (to escape the ship)

I’d add one more thing to that list. TENSION: (before it sinks) to include the ticking clock of the Poseidon Adventure.

Note: If you’re interested in digging even deeper, our Screenwriter’s Toolkit contains a Logline Matrix™ that helps you organize all the key elements so you can easily see them in one place. It practically writes the logline for you.

A logline is not a tagline

Taglines are short, snappy, and meme-like. They’re often indirect and sometimes sarcastic.

- In space, no one can hear you scream.

- They’re back!

- Who you gonna call?

- Don’t get mad. Get everything.

- With great power comes great responsibility.

- You’ll believe a man can fly.

- Houston. We have a problem.

- Be afraid. Be very afraid.

- A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…

All of those taglines. And it’s not our job to write them. They’re designed by marketing after your film goes through development and production. Don’t put them on your title pages or in your queries.

Finding inspiring loglines requires serious research

A problem for new writers is finding original loglines. Similar to the research challenge screenwriters face when seeking spec scripts, what’s easily found online isn’t exactly what we want to emulate.

For example, film descriptions we see on Netflix and other streaming services are not the loglines the writers used when querying, before the script was greenlit.

While we often point to those “TV Guide descriptions” film references and call them loglines, they are not. Yes, they fulfill a similar purpose: to describe the film in a few words.

But those are written for a completely different audience. The role of those movie blurbs is to tell potential viewers enough about the film so they can decide whether to watch it.

A writer’s logline differs in that its long game intent is to engage potential production interest. But its first job is to provide potential readers enough info about the story to entice them to read it.

Here’s a long list of great loglines from Screencraft to inspire you.

The logline in your queries is designed to sell

To put it another way, the purpose of a Netflix-type of blurb is to inform, whereas the logline in your queries is designed to sell.

Let’s look at the Poseidon Adventure again.

Here’s the general information blurb aimed at the viewing public, the TV Guide-type:

A group of passengers struggles to survive and escape when their ocean liner completely capsizes at sea.

Here’s the tagline on the poster:

Who will survive – in one of the greatest escape adventures ever!

And here’s a logline written following Chris Lockhart’s C-list, designed to interest a professional script reader and specifically to leverage a read-request:

When a tidal wave capsizes a luxury ocean liner, a rebellious preacher leads a handful of survivors through the deadly upside-down maze in their struggle to escape their underwater prison before the ship sinks.

See how they’re different? The first one, the blurb, tells us what it’s about – oh, a disaster movie on a boat. The second one, the tagline, tells us it’s exciting and might involve some deaths. The third one, the calling card/sales pitch logline, tells the situation, the protagonist, the obstacles, and the timebound stakes.

Winning queries always include an intriguing logline

Especially when cold querying, your logline must sing.

In the case of a direct query to a producer, the logline serves the same function as it does on a hosting site. But with a distinct difference.

When you respond to a direct call for scripts you know exactly what that particular producer is looking for. And if your IP sits passively on a hosting site waiting for producers to discover it, only those interested in your genre and logline will find it.

With a cold query, you’re the one reaching out. Blindly. Or nearly so.

Of course, you’ve done your research first. You’re not an idiot. You know that particular producer works in your genre. And you also know they accept unsolicited queries. But you don’t know what they’ve already got on their slate or in their pipeline. So an impossible-to-ignore and unforgettable logline is vital.

The one thing that can prevent summary deletion

Your logline will make or break your script. No “buts.”

The logline is the single thing that can prevent your email from unopened summary deletion.

Let me explain again, in case it still hasn’t sunk in. A logline has a solitary, specific aspiration. One. Like a headline, it seeks an audience. Unlike a headline, your spec logline has a much smaller, exquisitely targeted audience. Its only goal is to entice a single, well-positioned reader to request the full script.

Your script still needs to be awesome. But without a brilliant logline, it doesn’t have a snowball’s chance in upside-down hell of getting anyone to read even five pages. In order for your script to get read –never mind to advance– you need to hook one person with your scintillating logline.

Still don’t believe me? Try your own experiments. Pay for a month to host one script on InkTip. Load a solid logline and synopsis to accompany the full script and track the views. If readers are sufficiently intrigued to take it a step further and download your synopsis, you’ve done an excellent job on the logline. If they don’t, try tweaking it and see if those reads result in more interest.

Eventually, you’ll come to understand how that collection of a few, well-chosen words is your script’s best friend and can usher your foot through the narrowest of door openings.